Doing More with Less (like dogs)

Aug 31 2023

Getting the most out of your work and personal life.

This is a 3 minute read.

We all wish for more of something - more money, more friends, more time. Some of us might even crave more of everything. Sadly, the truth is that having more often makes us want even more. The initial excitement of something new fades away after a while, whether it’s days, weeks, or months. Then, in a vicious cycle, we’re onto the next new thing.

I see this happening all the time in my life and in the lives of others. We’re well aware of this reality. Apple does a great job of convincing me to trade in my perfectly fine iPhone for the latest model each fall. Their ads make us really want it. We tell ourselves, ‘The new camera is so useful, and it surely justifies the thousands of dollars I’m about to spend on the new iPhone Pro Max XR Ultra.’

How much happier would I be the day after getting the new phone? I’d probably feel pretty excited about my new phone with its new camera, screen, and all that good stuff.

How much happier would I be a month after getting the new phone? Probably not much happier than I was on the first day I’d reckon.

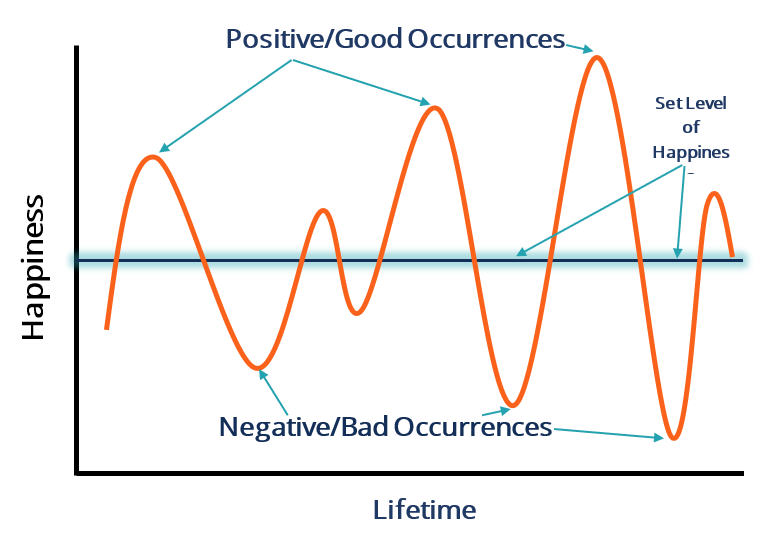

This phenomenon is called the hedonic treadmill1 or hedonic adaptation. It means humans tend to return to a stable level of happiness after extraordinarily good and bad events. Over our lives, we experience fantastic highs and tough lows, but we usually come back to a basic level of contentment. This can be shown on a graph like this:

So, how do we react to this information? Some of us might think, ‘Humans are quite tough. We can bounce back from dark moments pretty quickly with time.’ Others might wonder, ‘What’s the point of enjoying happy times if we’ll just end up less happy again?’

Both reactions make sense. My response to that is to enjoy the positive moments to the fullest, knowing you’ll probably return to a less happy state shortly after that really good event. On the other hand, knowing that difficult times will fade can make suffering a bit easier to bear, being sure that the light at the end of the tunnel isn’t so far away.

We can use a similar approach in our jobs, especially in tech. Imagine two options: reworking the entire architecture from scratch, or examining current resources for inefficiencies and room for improvement. Taking inventory of the current architecture first might reveal new insights and quick fixes to tough problems.

Completely redoing the architecture usually takes longer, needs staff training in new technologies, and might lead to downtime. It’s also quite expensive. On the other hand, finding areas to improve in the existing setup is usually quicker, cheaper, and easier. We can apply this to our personal lives too. Instead of seeking external solutions like alcohol, drugs, or shopping, we can reflect on what’s draining us internally and take the first step to improve.

(like dogs)

With all that said, dogs are really good at this hedonic treadmill thing. Dogs have to be some of the happiest creatures on Earth. Take my dog, Luna, as an example. Luna has only a couple of possessions: her collar and her favorite toy (named Gussy). She doesn’t need a new iPhone, she eats the same food, and does more or less the same things every day. Luna seems to maximize the happy moments, and quickly bounces back from a rut. Luna also doesn’t need new things in her life constantly to feel happiness.

Let’s try to be more like dogs in our daily lives.

Footnotes

-

Brickman; Campbell (1971). Hedonic relativism and planning the good society. ↩